Introduction

Seldom can prevalence have been so paradoxically matched by incomprehension,

or ignorance embarrassed by accessibility as in piles, for the disease is both

common and easy to inspect, and yet unnecessary confusion exists. There are two

reasons: a legacy of misleading terms related in turn to a misconceived

pathological explanation, and an inadequacy of anatomic description. Thus

disarmed by a stylized and simplistic image of anal anatomy and disabled by both

erroneous terminology and time-honored myths, the qualifying doctor can be

excused an inaccurate mental picture of what is in essence a simple complaint.

Given a true picture of the morphology of the anal lining, however, with an

understanding of its pertinent microscopic features one can readily perceive

both what piles are, how they occur, and what they would look like, and be able

to predict and envisage the complications to which they are prone.

The names 'haemorrhoids' and 'piles' are essentially synonymous though

differently derived from the two main—and only certain—symptoms, respectively

bleeding and protrusion. The disease, though, is not the result of varicosity

nor, as the reader will appreciate, are itching and pain its necessarily

expected accompaniments. All this, and their logical management, will become

clear from the anatomic account.

Anatomy of the anal lining

The anal canal is usually shown as a 4-cm long tube lined in its upper

two-thirds by insensible mucosa and below by a hairless, glandless cuff of

highly sensitive squamous epithelium, the anoderm. The mucosa is seen to be

thrown into longitudinal folds (named after Morgagni) which are

sometimes—incorrectly—depicted as containing vertically ascending columns of

serpigious veins. This oversimplified description derives from the usual method

of preservation and dissection and provides no clue either to the intricacies of

its infrastructure or the almost inevitable vagaries of its existence .

If, instead, the vessels of a fresh anorectum are filled (retrogradely, from

the superior rectal vein) prior to inflation and fixation, the interior of the

anal canal is seen, on transection of the rectum above, to look quite different . Now the anal lining

bulges into the lumen as three (occasionally four) pads—each more or less

impressed by the vertical mucosal folds—which have been called the anal

cushions. Their presence and curious architecture are the key to piles.

The anal cushions

Nineteenth-century anatomists gave a more accurate and detailed description

of the anal lining. One feature they recognized was the thickness and rich

vascularity of the anal submucosa. It was in fact likened to cavernous tissue

and reckoned to assist anal closure. The observation of its discontinuous

grouping into three main and constantly sited masses, however, explained the

nature of piles. We called them the anal cushions. There is often a fourth

midline posterior one and their substance extends above and below the dentate

line. When their component vasculature is filled they confer an appearance to

the anal lining which belies the standard anodyne description .

Blood supply

The anal cushions receive a rich intercommunicating supply from the superior,

middle, and inferior rectal (synonymously called haemorrhoidal) arteries. From

five to eight branches of the superior rectal artery pass from the mesorectum through muscular 'button

holes' in the rectal ampullary wall to descend into the anal submucosa , there to anastomose freely

with contributions from the middle and inferior vessels. Local mucosal

excisional procedures will inevitably encounter substantial bleeding from any

one or all three sources. Part of this supply is carried straight into the

venous system by direct arteriovenous shunts and probably provides for the

mechanical function (described below) without which the wealth of vasculature is

not fully explained.

The veins of the anal submucosa are particularly notable, exhibiting one of

the two entirely unique local morphological characteristics. They are

distinguished by discrete dilations along their course, particularly

subanodermally. These vein sacs, resemclover root, were once thought to be

pathological, and in fact the underlying fault in piles. John Hunter (1728–1793)

described them in a haemorrhoidectomy specimen (Spec. 1277, Hunterian Museum,

Royal College of Surgeons of England) and noted the great curiosity of their

being separated by segments of normal vein . They are, however, normal. They

occur in all adults and are found at birth . The subanodermal sacs look like

petals of a blue daisy through the skin of a baby's distracted anal verge, and

can also be demonstrated in the adult . They drain mainly cephalad into

the portal system but also through the sphincter and below it into the systemic

circulation; a route, though, that dissections suggest becomes increasingly

tenuous with age , which might explain the

postdefaecatory anal verge engorgement and oedema that troubles some patients,

and the oedema and discomfort of some prolapsed piles.

Support

The cushions are held against the shearing, extruding force of defaecation by

smooth muscle, the musculus submucosae ani, and by elastic tissue. This muscle,

the second unique anatomic feature—nowhere else is muscle to be found in the

submucosa—was discovered by Treitz (1853) and has been observed and drawn by

others since. It descends from the internal sphincter in separate bundles which coalesce subanodermally

to form a dense supporting stroma around the vein sacs . A longitudinal section shows its full extent and demonstrates how the looser

upper part of the cushions is supported by the tough more strongly secured lower

component, and how the muscle's contraction, which occurs during defaecation,

both flattens the cushions and braces them against the internal sphincter.

Function

There can be no doubt that the anal cushions contribute to anal closure. The

spongy substance and variable volume conferred by the vein sacs, with their

direct arterial communications, imparts an appropriate texture—firm, too, below

and floppy above—upon which the sphincter can 'squeeze' to complete closure. Of

interest, an inner tube of an inflated tyre falls naturally into three parts if

a band around its perimeter is tightened (David Tibbs, John Radcliffe

Hospital—personal communication).

The nature of piles

The anal cushions can as we have seen be viewed from above in an

appropriately prepared specimen . They can also be seen

anoscopically , in transverse histological section (, and by holding the dissected-free anal lining

up to the light . By whatever means of demonstration they are found

constantly to occupy the left lateral (3 o'clock), right posterior (7 o'clock),

and right anterior (11 o'clock) sectors of the anal circumference, and not

infrequently the posterior midline, which of course is where piles present. It

is logical to conclude, therefore, that the condition we call piles or

haemorrhoids results from the internal disruption and downward displacement of

the anal cushions, a conclusion supported by both their macroscopic and microscopic appearance . Varicosity of the anal veins, when it (rarely)

occurs, looks quite different.

Pathology

The anal cushions are disrupted to produce piles by the forces of

defaecation. For many sufferers defaecatory habits and stool consistency are

probably to blame. The Valsava effect of excessive straining engorges the

cushions, which have lost the support of the external sphincter as it relaxes.

The shearing force of hard stools will increase the damage. In other patients

who claim a lifetime of regular easy bowel actions, the anal cushions may be

structurally deficient. Weakness arising from the influence of progesterone on

smooth muscle and elastic tissue may explain the predisposition to haemorrhoids

in pregnancy, though an increase in pelvic vascularity may contribute. Many

women date their haemorrhoids not to actual pregnancy but to parturition, when

the supporting tissues of the anal cushions may be stretched and torn.

Histological examination often shows larger vascular spaces than normal and

more prominent connective tissues but no changes not accounted for by the

effects of disruption.

Classification

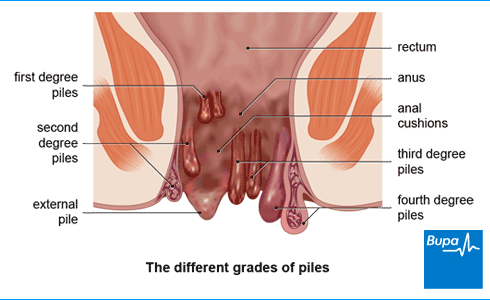

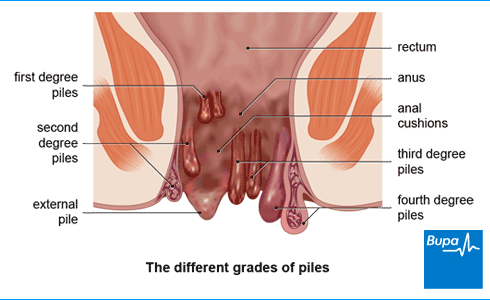

It is customary to classify haemorrhoids by degree: first degree, only

bleeding announces their presence; second degree, spontaneously reducing

prolapse at defaecation; third degree, prolapse requiring manual replacement;

fourth degree, permanent prolapse. However, while a classification is required

for the purpose of comparing different treatment techniques scientifically, the

degree of any particular patient's piles may in fact vary with time.

The terms 'internal' and 'external' piles add little.

Symptoms

Although the underlying lesion in piles—disruption of the supporting and

anchoring tissues of the cushions—means that prolapse is inherent in their

nature, bleeding is more worrying and is the usual reason for seeing a doctor.

Prolapse is, however, the other unequivocal symptom. Pain, itching, and anal

dysfunctional effects are less reliable diagnostic criteria.

Bleeding

The capillaries of the lamina propria are only protected by a single layer of

epithelial cells, and little trauma is required to breach them. Since it is the

more lax-textured, upper part of the anal cushion which mainly prolapses,

dragging the mucosa to the outside, trauma due to wiping or contact with clothes

often occurs. Repeated trauma produces a chronic inflammatory response, making

the damaged mucosa a brighter red, and granular and so more friable and likely to bleed.

A great deal of unnecessary investigation, which is costly, inconvenient,

uncomfortable, and occasionally even hazardous for the patient, can be avoided

by time spent unravelling exactly what is meant by bleeding. Patient and

courteous attention to detail in taking a history is always amply repaid, but

never more so than here: haemorrhoids are very common, and yet bleeding may also

indicate a more serious condition. First- and second-degree piles, which remain

intra-anal except at defaecation, bleed with the bowel movement. Being capillary

blood it is bright red. If enquiry reveals that it occasionally drips, an anal

origin is certain, because the anus remains closed by tonic contraction of the

sphincter except at the moment of defaecation. Blood that drips into the pan,

after passage of the stool, must originate either from extruded anal mucosa, or

from a fissure in the anoderm. The only other, and most uncommon, possibility is

a rectal polyp on a long enough stalk. Similarly, bleeding into clothing is

almost certainly of anal origin. Blood smeared on the stool in the pan is

ominous and unlikely to be coming from piles, since freshly shed blood ought to

disperse into the water. The fact that it remains on the stool suggests either

that it has congealed there, or is mixed with mucus, indicating a higher

lesion.

Passage of clotted blood also demands exculpation of a colorectal source, and

a careful history may provide a useful clue. Piles may still be the explanation

if questioning reveals that the clots were only seen on the paper; such clotting

can have occurred in freshly shed blood lying at the anal verge. It is very rare

for a large pile to bleed back into the rectum and proclaim itself by passage of

older clots at stool.

Prolapse

Many patients have not tried manual replacement of their piles after

defaecation, having been 'afraid to', and therefore put up with more discomfort

than they need. Others replace them promptly only to be demoralized and

inconvenienced by their messy extrusion on exertion later.

Pain

Pain is a contentious issue in pile symptomatology. Although claimed to be a

prominent and attributable problem, there seems to be no good reason why a

disrupted anal cushion should actually be painful. When trapped outside the

closed anus, distortion combined with oedema and congestion from lymphatic and

venous impairment may well cause discomfort. In many cases pain on defaecation

is due to an easily overlooked fissure. None the less, some patients do

experience relief from what they had thought of as pain from successful

treatment of their uncomplicated piles, and the wise clinician allows for some

hyperbole, perhaps, in description.

Episodes of painful irreducible swelling which last a week or so can be most

unpleasant. Often called 'strangulated' piles or an 'attack of the piles', they

are usually due to greater or lesser degrees of infarction resulting from

obstruction of venous drainage by thrombosis and consecutive clotting in the

sacculated venous plexus. Infarction is used here in its proper sense, denoting

an intravascular and interstitial 'stuffing with blood', and not in its common

contemporary misusage implying necrosis. Although necrosis would supervene if

circulatory impairment by venous blockage were sufficient, complete obstruction

of venous return is in fact very rare and the usual outcome is spontaneous

resolution as the clot shrinks and lyses and venous circulation is

restored.

Itching

When the patient's main concern is itching, piles are seldom to blame. A

local skin condition is usually responsible. Although treatment of coexisting

piles may procure relief, it is unwise to encourage a patient greatly bothered

by pruritus to believe that the answer is at hand. Mucus discharge from a

prolapsed pile, however, causes an alleviable irritation in some patients.

Anorectal dysfunction

Defaecatory derangement can be excited by disrupted anal cushions causing a

sensation of incomplete evacuation, particularly when further engorged by

fruitless straining. Of course a feeling of unsatisfied defaecation—tenesmus—may

have a more serious explanation.

Soiling

Blood and serum from the exposed inflamed mucosal part of a pile dries dark

on underclothing and may be thought fecal. Only very rarely, however, do third-

and fourth-degree haemorrhoids allow minor conduction of rectal contents to the

surface. Mucus may also exude from the exteriorized mucosa of piles and can be

the presenting symptom.

Examination

When a meticulous history suggests piles and the findings agree, examination

can be confined to the anorectum. The only equipment then required is

proctoscope (anoscope), rigid sigmoidoscope (rectoscope), light source, and

biopsy forceps. Many, however, would disagree and argue for routine adjunctive

fiber-optic inspection of the distal colon, at least in those over 40 years of

age for rectal bleeding, however described and whatever the anoscopic findings.

Some workers in this field indeed advocate full colonoscopy in patients aged 40

or over presenting with rectal bleeding even when bright red, on the basis of

the frequency of finding right-sided pathology in those of middle age and older,

but in the author's view theirs is more an argument—still unresolved—for

screening.---buasir.jpg)

---buasir.jpg)

Signs

There are several dynamic influences on a pile's presentation—the vigorous

arterial supply, the presence and possibly changing diameter of the

arteriovenous shunts, the variability of cushion bulk due to the capacity of the

venous saccules, and the effects of cushion displacement and anal sphincter

contraction on venous and lymphatic drainage. As a result, not only does the

appearance change from time to time in the same patient, but the same symptom

may have different causes. For instance, whereas most people complaining of

prolapse have simple displacement of the anal cushion(s) , a 'lump' felt by others may be

due to engorgement of the subanodermal veins from, one presumes, impaired

drainage or transient but most uncomfortable postdefaecatory

anodermal oedema. .

Piles that are transiently displaced suffer little trauma, but when the

mucosal part is frequently exposed it becomes inflamed . Thrombosis and clotting in the vein sacs also

influence the appearance of the pile, but as an indication there will be

associated discomfort or, depending on the extent of clotting and consequent

infarction, frank pain. Clotting of a small part of the venous plexus causes an

uncomfortable attack of swelling of the pile, with oedema but little infarction.

Greater degrees of obliteration of venous drainage embarrass the circulation

accordingly . However, even the fully infarcted pile will, despite its appearance, resolve. Many patients

who seek medical attention because of such an attack of saccular clotting, and

who graphically describe the severity of the condition, have recovered by the

time of specialist consultation. The term 'strangulated piles' may be misapplied

to this condition, causing inappropriate and inevitably unsuccessful efforts at

supposedly therapeutic replacement.

A disordered cushion may, therefore, present in one of several ways as a lump

at the anal verge. Commonly, however, external inspection provides no clue to

their presence, and nothing abnormal is found on anal digitation, since

uncomplicated piles are impalpable. A nodular induration is felt if clotting has

occurred. In most patients, the diagnosis is suggested by the history and

confirmed with the anoscope. Interpretation of the appearance is not

straightforward. Since anal cushions are normal structures , their distinction from piles is only one of degree. Bright red granularity of the

mucosal part of a cushion is certain evidence of its disruption, and the extent

to which the cushions bulge into the instrument's end on straining and follow it

out on withdrawal, provide a valuable guide. The beginner will often miss the

anoscopic diagnosis of piles from failing to ask the patient to push down as if

defaecating as the instrument is gradually withdrawn. A previously unimpressive

anal cushion may then demonstrate its obvious disruption.

Rectoscopic (rigid 'sigmoidoscopic') exclusion of rectal disease is an

essential part of the establishment of the diagnosis. Because piles are common,

finding them does not rule out another condition higher in the rectum causing

the symptoms. There is, however, no evidence for the claim still occasionally

made that haemorrhoids can result from rectal carcinoma or pelvic masses.

Differential diagnosis

Anal tags

Many patients mistake anal tags for piles, and indeed the disrupted anodermal

part of a cushion may have a similar appearance. Anal tags are cutaneous

protruberances at the junction of the anoderm and perianal skin. They are of

uncertain origin, but possibly result from local derangement of lymphatic

drainage—as their occasional disarming partial reformation soon after excision

suggests. They can be solitary and discrete, or form a circumferential irregular

fringe .

Fibroepithelial polyp

These are club-like protruberances from the dentate line and seem to be

hypertrophied anal papillas, again possibly due to lymphatic obstruction .

Sentinel pile

This misnomer is given to a skin tag marking—and often containing within

it—the distal end of an anal fissure, found usually in the posterior midline .

Fissure

A patient described as having 'painful itchy piles' may well be suffering

from an anal fissure, particularly when associated with a sentinel tag

masquerading as a pile. The deep burning pain of a fissure on and after

defaecation and the associated itching are quite unlike the discomfort

appropriate to a pile. Typically, too, the pain of a fissure will start some

30 min after defaecation and continue for 2 to several hours.

Dermatitis

Because of the widespread belief, both in the lay and the medical mind, that

itching and soreness mean piles, in many patients referred for a surgical

opinion the problem is in fact dermatological. Hyperkeratosis (seen as pale,

slightly soggy or glazed skin), erythema, punctate excoriations, and multiple

hairline radiating cracks—often more pronounced in the anterior or posterior

midlines—will suggest the correct diagnosis . While the occasional patient

may have psoriasis and quite a few are prone to itchy rashes elsewhere, in most,

in the author's experience, the problem is confined to the anus. The pain at

defaecation of anodermatitis usually lasts only a matter of seconds.

'Perianal haematoma'

The term 'pile' might easily have been inspired by this condition (Latin:

pila = ball) so spherical and usually singular is it , and its other name, 'thrombosed external

pile', is not entirely inappropriate. However, to keep our terminology exact we

should use 'pile' to denote a disrupted anal cushion. These often painful

lesions of sudden onset and, when not relieved by incision, of usually

self-limiting nature (either by rupture or by absorption) are not in fact the

ruptured blood vessel the term suggests (nor are they strictly speaking

'perianal', arising as they do subanodermally) but vein sacs distended by clot.

The term 'clotted vein sac' describes them accurately but though preferable is

unlikely to supersede its time-honoured alternative.

Rectal prolapse

Early rectal prolapse may be confused with piles when the patient is unable

to describe the size of the protrusion and is inhibited from straining

sufficiently at the examination to produce it. Treatment for piles may then be

instituted with later disappointment, but no substantial harm done.

Rectal tumour

Rectal tumour can easily be missed by impatient history taking and

unreflective digital examination, for it is not so much the length of the finger

which matters as the amount of thought behind it. Because of the rectum's

curvature, even upper-third tumours may be palpable. Even when nothing is felt

or seen, if the patient's symptoms do not accord with the findings further

investigation is required. Ominous symptoms are old blood, particularly if slimy

or clotted, tenesmus, altered bowel behaviour, deep discomfort, and

'wet'—messy—flatus.

Miscellaneous

It is a curious fact that almost any discomfort in or irregularity of the

anorectum may be attributed to piles. Thus proctalgia fugax, proctitis, solitary

rectal ulcer, fistula-in-ano, and warts may also all masquerade.

Treatment

Since piles may be blamed for almost any anal condition the first step is to

decide whether they could be responsible for the symptoms. When itching is the

main complaint piles are unlikely to be the cause, and actual pain—rather than

the discomfort of protrusion or episodes attributable to attacks of

thrombosis—is more likely to be due to a fissure. Chronic anal pain, of course,

is never due to piles. With prolapse and bleeding, however, we are on firmer

ground.

The management will be either conservative or interventional.

Conservative treatment

Although piles are by definition disrupted anal cushions, symptoms from them

are partly determined by their size, which can alter greatly depending on the

state of engorgement of their constituent vein sacs, which in turn is affected

by straining and the state of tone of the surrounding anal sphincter. Simple

avoidance of prolonged straining at stool may achieve sufficient symptomatic

relief. An increase in dietary fiber, therefore, and desistance from reading in

the lavatory, together with advice to ignore the false signal suggesting the

need for a greater straining effort imparted sometimes by prolapsing piles may

be enough.

Interventional treatment

Surgical measures work by reducing the bulk of the disrupted anal cushion

(not only has its attachment loosened but its internal structure as well), and

inducing adhesion of the remainder. Since the mucosal part causes most of the

symptoms—all of the bleeding and mucus discharge, and most of the discomfort—its

reduction will be sufficient for the majority of patients. Even a large

cutaneous component may be pulled up and so be flattened and tidied by tissue

reduction above. It is therefore fortunate that the mucosa is insensitive and so

allows quick and effective treatment in the outpatient clinic or office. Various

techniques are available.

Rubber band ligation

In 'banding', as it is called, a 'polyp' of the pile centred sufficiently

cephalad to prevent involvement of the sensitive anoderm is pulled into a

ligating device passed down the anoscope and strangulated by displacing from the

ring-mounting a small rubber O-ring previously rolled there from a cone loader.

The incorporated tissue withers and falls away within 2 or 3 days leaving a

small ulcer which is usually healed in a month.

The size of the 'polyp' banded will depend on the toughness of the tissue,

the volume of redundant loose cushion, and the traction force applied by the

operator. Previous intervention—banding, injection, and so on—may cause such

dense scarring as to prevent the incorporation of sufficient tissue to help.

Usually, however, with good grasping forceps a polyp the size of an average

raspberry can be banded, and sometimes, gratifyingly, the size of a large one.

Because the anatomy of the anal canal and the mechanics of banding make it

impossible to ablate enough tissue to be damaging, the author takes the view

that the greater the volume of the mucosal part of the pile which can be

ensnared the better. The pile is therefore first carefully 'sized up' down the

anoscope to choose the site to be seized by the graspers which will ensure the

strangulation of the greatest part of the pile without involving the anoderm. If

the amount of tissue obtained seems less than expected, a further application,

this time firmly grasping and pulling on the previously banded polyp, will often

achieve more . If on the other hand the band looks to have been

placed too high or too low, a further adjoining application is worthwhile .

Even permanently prolapsed irreducible piles can be cured by banding. The

band can be applied to the exposed mucosa outside the anal canal with complete

symptomatic relief, even the cutaneous/anodermal element being improved, and

anyway seldom much of a nuisance .

Several banding instrument models are available and although they work on the

same broad principle there are two main categories, single-operator and

assistant-required. As well as their self-evident attraction, single-operator

banders confer the advantage that in holding the proctoscope throughout the

surgeon can keep it exactly on the selected target. There are three types. One,

a suction device (which can be driven by the Venturi effect of a running tap),

uses a metal sucker tube—with the banding rubber ring mounted at its end and

displaceable by a trigger—to suck the pile to which it is applied (under vision

down any proctoscope) into it. Although straightforward to use, the need for

suction may create practical difficulties, and the impossibility of knowing how

much tissue has been sucked into the end for banding and how much suction can

safely be applied without causing avulsion are deterring factors. Another

consists simply of a small-diameter proctoscope with the rubber O-ring, again

displaceable by a releasing mechanism, mounted at the operating end. A

theoretical disadvantage to its use may be the problem of inadequacy of view.

The 'One-man bander' seems to overcome both these disadvantages . Several loaded ones are kept ready so that even

multiple banding can be the work of a moment. It is designed for use down the

Naunton-Morgan 'rectal speculum', a proctoscope, in fact, whose wide diameter

allows a more certain diagnosis of piles than those of smaller bore (which may

prevent their appreciation through providing too narrow a view). It is certainly

the author's experience that piles can easily be missed down narrow

anoscopes.

For grasping the pile, Irvin-Moore's nasal conchal forceps seem ideally

suited. They open more widely within the ring of the ligator than at least one

purpose-designed model, and grip the tissue with less danger of tearing .

On a note of caution, it has been the author's experience that combining pile

banding with an anal stretch procedure may precipitate clotting in the residual

sacculated venous plexus and so cause severe anal cushion infarction with its

associated pain and swelling.

An empty rectum making banding easier and certainly more agreeable if not

safer, it is best to have the patient self-administer a mini-enema or glycerin

suppository prior to the banding. In addition, in case any pain afterwards would

otherwise inhibit defaecation, it is sensible to advise patients to start a

week's course of ispaghula husk or similar the day before. Finally, to make the

procedure and its immediate aftermath as comfortable as possible the patients

are also given analgesic tablets to take an hour before, and a supply to use

afterwards.

Infrared photocoagulation and bipolar diathermy

Both of these cause tissue destruction by heat. The instruments are applied

through an anoscope to coagulate a predictable volume of adjoining tissue. The

mucosal part is treated so no anaesthesia is required.

In bipolar diathermy the mucosa is simply grasped by the instrument and the

intervening tissue destroyed by an electric current passed across from one

electrode to the other.

Sclerotherapy

An irritant chemical solution, usually 3 ml of 5 per cent phenol in arachis

oil, is injected into the submucosa of the mucosal part of each pile. When the

varicose vein theory of piles prevailed it was thought to act by inducing

fibrosis which constricted the superior rectal venous drainage, so, it was

thought, deterring the causative—as they thought (from the human's erect

posture)—transmission of the supposed high pressures from the portal system. In

fact it probably causes shrinkage of tissue by necrosis, and adhesion as a

result of the ensuing inflammatory reaction.

Cryotherapy

A liquid nitrogen probe is placed against the pile for 3 min, and causes cold

necrosis. Local anaesthesia, at least, is said to be needed.

Laser treatment

Laser evaporation has also been used for pile excision, with good initial

reports. Its theoretical attraction lies in the reduction to the minimum of

damage to residual tissue. However, it is an elaborate way of performing a

simple task and uses expensive and fallible equipment in a forgiving area of

great blood supply and margin for error in which excellent results can be

obtained by simpler means. Were it to prove significantly less painful than

scissor excision, and perhaps to allow more rapid healing, neither of which has

so far been shown, then it might find widespread use.

Haemorrhoidectomy

When the troublesome cutaneous part of a pile is too large or immobile for

patient relief simply from addressing the mucosal moiety above, scissor

excision—haemorrhoidectomy—is required. However, although not 'ambulant', it is

therapy that can often be done under local anaesthetic and seldom requires much

more than an overnight stay. The excessively painful and prolonged experience of

folk memory resulted mainly from the well intentioned use of wide-bore rubber

drains or packs inserted in theater against the risk of haemorrhage. Mistaken,

too, was the much encouraged belief that three-sector excision was always

required ('the operation's over when it looks like a clover'), a practice

unfounded in either trial or systematic experience. It arose with little doubt

from the appearance of even normal anal cushions after anal manipulation in the

lithotomy position, particularly when a patient is 'light' and strains under the

anaesthetic. In fact the surgeon should be guided by the disease and will

therefore sometimes excise in only one place, although in other cases in four.

Always, however, adequate bridges of healthy tissue must be left between

excision sites because not only is the anoderm of great functional importance in

continence—'sampling' the rectal contents before release—but its excessive

removal will result in a stricture, an avoidable tragedy. The other half of the

mnemonic is certainly true, 'if it looks like a dahlia it'll end up a

failure'.

The patient's rectum should be emptied prior to surgery by means of an enema

administered about 2 h before. Whereas in the United Kingdom the patient is

usually put 'in lithotomy' for the procedure, the prone jack-knife position is

probably preferable for reasons both of access and local conditions, the anal

canal's axis then being in a line with the surgeon's eye rather than, as in the

lithotomy position, at an angle to it, and the vasculature not being unnaturally

suffused with blood. However, the lithotomy position and the lateral position

with buttocks taped apart, also useful, are easier to arrange.

Haemorrhoidectomy can be performed either open or closed and is done with

scissors or diathermy (or for that matter, laser). Either way, the essential

principle, emphasized by the reminder that surgery is the replacement of one

lesion by another, is to keep the damage to the minimum required for symptomatic

relief. Remember, too, that piles are just overlarge, floppy, and displaced

parts of a structure which almost certainly contributes to anal control, so

excision should leave sufficient behind. Above all, ample 'bridges' should be

left. Finally, the midline anoderm, particularly posteriorly, being so unstable

and prone to fissure, it is as well to stay away from it. Therefore, a

symptomatic midline posterior pile, as can occur, may be better treated by band

ligation—so above the dentate line—with acceptance of any residual cutaneous

irregularity there.

Open—excision/ligation—haemorrhoidectomy was popularized by Milligan and his

colleagues at St Marks Hospital, London. Forceps are applied to the cutaneous

part of the pile at the anal verge to reveal the mucosal moiety. A second pair

then grasps the main pile mass which is thereby lifted from its surroundings. It

is then snipped from the adjoining skin in a racket-shaped cut whose wide

handle, directed cephalad above the dentate line, contains the superior rectal

contribution to its blood supply . The elliptical part of the cut overlying the

intersphincteric groove passes through the subanodermal part of the

haemorrhoidal venous plexus to reveal the discrete vein sacs within. It is

deepened to reveal the lower border of the internal sphincter. The pile is then

dissected from the internal sphincter for a few millimetres (emerging fibres of

Treitz's muscle will be encountered and divided)—both by identifying to

safeguard it and to allow ligation above the dentate line (so of insensitive

tissue)—so creating a thick pedicle which is transfixed and ligated . The ligated remnant—most is excised—falls away in

a few days to allow the open wound to heal by secondary intention. Despite that

much diathermy coagulation may be required at the edges to achieve haemostasis,

the wound usually contracts rapidly and will be found almost closed in as little

as 10 days.

The closed method, with or without submucosal excision of adjoining

'haemorrhoidal' tissue, was designed for faster healing and less pain. (The term

'haemorrhoidal' here illustrates the confusion which misleading terminology

engenders. The spongy cavernous-like submucosa of the anal canal serves a

valuable function in continence. Calling it 'haemorrhoidal' suggests disease and

so encourages excision). It has not, however, been shown to achieve either aim,

neither pain relief nor healing being improved. (Confoundingly,

haemorrhoidectomy was also no more comfortable after a smooth muscle relaxant or

internal sphincter division (lateral sphincterotomy)).

By operating down a wide-diameter slotted speculum the pile can be excised in

its anatomic position without distortion, a technique which recommends itself

from first principles alone. The pile exposed in the slot is excised within an

ellipse, exposing the internal sphincter in its base, narrow enough to allow

closure without tension . It is a technique which has been found most

satisfactory.

After haemorrhoidectomy by whichever method, light dressings are placed over

the anus, perhaps kept in place by elasticated pants for easy changing. If

general anaesthesia has been used the anal wounds should be thoroughly

infiltrated with a long-acting local anaesthetic. The anus should not be packed.

Warm baths are comforting, with or without salt, and measures are taken to keep

the stools soft and regular. There is no need for the patient to stay in

hospital until the bowels have moved but if they have not by the third day the

patient should report back for an enema. Antibiotic cover is not required unless

there is a particular predisposition to sepsis.

Manual anal dilation

This was widely practised as a treatment for piles in the last century. The

nineteenth-century French surgeon, Verneuil, again reconciling its effect with

the varicose vein theory, thought it improved venous drainage by stretching the

rectal muscular button holes which convey the anal tributaries of the superior

rectal vein. When reintroduced some years ago, it transiently displaced the

surgical standby of the time, haemorrhoidectomy, but was later shown to have

limited application. It probably helps patients who have discomfort and

difficulty in defaecation by easing the effort of evacuation, so reducing the

congestion of the cushions from excessive straining.

Pile stitching

This has been advocated. Absorbable sutures are placed above the dentate line

to attach the cushion back to the internal sphincter. Obliteration of its blood

supply also reduces bulk. It has a place when large piles demand amelioration

yet there is a substantial risk from haemorrhage—in the presence of a cavernous

haemangiomatous deformity, for instance, or when a patient must not discontinue

anticoagulants.

Complications

Ephemeral

Vasovagal

A few people—mainly young males in the author's experience—faint after

banding of piles, and even injection. It is therefore sensible to warn all

patients to arrange to be driven home.

Pain

Some discomfort follows all the tissue ablative procedures but amounts in

some patients to severe pain lasting as long as a week. Again, prior knowledge

will prevent much needless worry and also allow the patient to plan in

advance.

Haemorrhage

Tissue destructive or excisional techniques will also leave a well

vascularized, raw wet surface and so carry the irreducible risk of secondary

haemorrhage. It is rare, but when it occurs, alarming, but once more if the

patient is told of the possibility beforehand there will be less anxiety and

disruption. In the author's experience only once in 20 years has continued

bleeding required suture for haemostasis. In the other dozen or so instances the

bleeding stopped spontaneously and without resort even to attempted tamponade

with a balloon catheter. A micronized flavonidic fraction of diosmin and

hesperidin (Daflon) significantly reduced secondary haemorrhage in one trial,

and in an experience of 12 patients with secondary haemorrhage after

haemorrhoidectomy a submucosal injection of 1:10 000 epinephrine through a

proctoscope under sedation secured haemostasis each time.

Infection

Sepsis is an uncommon complication and will be treated on its merits. Fatal

sepsis even after simple banding has been reported in immunocompromised

patients. Stories are handed down of portal pyemia following haemorrhoidectomy,

and of necrotizing fasciitis complicating it. Both no doubt have occurred and

will again but must be excessively rare. Neat surgery with the least trauma will

surely reduce the possibility as will patient selection and judicious drainage

rather than skin closure when the tissues have been compromised.

Urinary

Haemorrhoidectomy is notorious for causing transient difficulty in voiding in

men. Banding may also induce curious bladder symptoms. Inadvertent intra- or

periprostatic injection of sclerosant may have serious sequelae, even impotence

being reported.

Anal cushion thrombosis

Occasionally, excessive pain seems to be attributable to thrombosis/clotting

in the residual anal cushion after pile banding, the complication being

detectable by the digital discovery of knobbly induration within the anal

canal.

Permanent

Impairment of continence

A thorough study of 172 patients who had undergone haemorrhoidectomy at least

3 years previously (at a time when three sector excision was standard) found

that 26 per cent had experienced a consequent impairment of control. Given the

function of the anal cushions and the fact that haemorrhoidectomy may have been

relegated to the end of the operating list to be performed by an unsupervised

trainee, this outcome is not greatly surprising. However, if the surgeon

confines tissue removal to the clearly redundant and leaves what Waldeyer called

the 'corpus cavernosum recti' substantially intact, no functional impairment

need be feared.

Oedema and tags

Occasionally, however careful the excision, the intervening skin bridges may

swell uncomfortably with oedema to remain afterwards as tags. Though lymphatic

impairment, perhaps from diathermy damage, is presumably responsible, the

aetiology of anal tags is obscure; furthermore, when the entire anal lining has

dislocated to form a circular curtain at the anus, the intervening bridges will

of necessity remain as tags. They can be improved later under local anaesthesia

if required.

Stricture

The anal lining is extraordinarily forgiving; elastic, robust, and quick

healing. Only inexcusably excessive excision will result in stenosis, or some

other extraordinary circumstance.

Which treatment?

A generation ago the choice was limited; for bleeding there was injection,

and for prolapse haemorrhoidectomy. Nowadays open surgery is seldom necessary.

The invention of outpatient tissue-reducing techniques has not only increased

the possibilities but improved the prospect. At the same time the introduction

of prospective randomized clinical trials has for the first time enabled

scientific evaluation.

Conservative treatment has been compared with band ligation; bulk purgatives

or high fibre diet with sclerotherapy, stretching, sphincterotomy, band

ligation, and freezing. Banding has also been compared with sclerotherapy,

haemorrhoidectomy, stretching, and infrared photocoagulation. Photocoagulation

has been compared with bipolar diathermy, and one type of haemorrhoidectomy has

been judged against another. Excellent and praiseworthy though such trials are

they suggest a 'rivalry', when in fact no one treatment is best for all

patients. Their greater merit is in showing prospectively and with careful

control and monitoring that benefit can be derived from each measure, so

allowing us an informed choice of the possible treatments.

However, while infrared- and electrocoagulation achieve the same objective

with less pain and time off work, band ligation requires significantly fewer

treatment sessions, and the instrument used is both cheaper and more robust.

Multiple banding having been shown to be no more painful than a single

application per visit, in the author's experience the great majority of patients

are put right at one attendance. A recent overview, in fact, concluded that

rubber-band ligation was the most effective 'ambulant' measure available.

Haemorrhoidectomy though requiring admission, anaesthesia, and a longer

recovery, still retains its place when the cutaneous part of the pile is causing

the problem. Careful and targeted surgery will be rewarded by an excellent

result and a most satisfied, relieved patient.

Cryodestruction is an anatomically less accurate means of tissue ablation and

leaves a smelly, weeping wound slow to heal. Laser surgery offers attractive

qualities but, given the rapidity of both doing and recovering from simple

scissor excision and the cost of the equipment required, it seems unlikely to be

preferred.

Manual anal dilation may have the occasional adjunctive place in the

management of piles but would no longer be advocated as primary treatment.

Management of infarcted ('strangulated') piles

When one reflects on the necessarily turbulent flow in the sacculated venous

plexus it seems odd how seldom thrombosis and clotting occurs. Afflicting a pile

it causes considerable swelling and discomfort, and invites attempts at

immediate amelioration. However, there have not been, and are unlikely ever to

be, randomized trials of conservative and surgical treatment. In the author's

experience the infarction is only rarely so dense as to cause insupportable pain

and lead to necrosis, so most patients can be reassured that natural

thrombolysis will restore the circulation and result in resolution in about

10 days . Nitroglycerin ointment is reported to provide

dramatic relief from the pain. In severe cases, however, there is no doubt that

debridement haemorrhoidectomy, excising the worse afflicted tissue, is rewarded

by rapid deliverance from misery .

For the majority sufficient relief will be obtained by rest, analgesics, and

hot baths, and by the medical attendant's confident prediction that the worst

will be over in a week or at the most 10 days. Meanwhile they will be best

advised to ensure soft regular stools by the daily consumption of ispaghula husk

or its alternatives.

Conclusion

Once one understands the detailed anatomy of haemorrhoids and their

pathological possibilities, their management is straightforward, and the

treatment effective, acceptable, and reasonably trouble free. The important part

is diagnosis. The patient's preconception that piles are responsible for their

symptoms must not cloud the clinician's mind, for it does not take long

experience in a busy anorectal disorder practice to realize that many patients

sailing under the pennant of piles have something functional, dermatological, or

otherwise idiopathic causing their symptoms. Uppermost must be the question

whether reducing the bulk of the anal cushions and mooring them more firmly will

logically address the presenting problem. If not, then in a nineteenth-century

surgeon's words, 'in such cases prudence equally forbids the rash interposition

of unavailing art, and the useless indulgence of delusive hope'.

After being in relationship with Wilson for seven years,he broke up with me, I did everything possible to bring him back but all was in vain, I wanted him back so much because of the love I have for him, I begged him with everything, I made promises but he refused. I explained my problem to someone online and she suggested that I should contact a spell caster that could help me cast a spell to bring him back but I am the type that don't believed in spell, I had no choice than to try it, I meant a spell caster called Dr Zuma zuk and I email him, and he told me there was no problem that everything will be okay before three days, that my ex will return to me before three days, he cast the spell and surprisingly in the second day, it was around 4pm. My ex called me, I was so surprised, I answered the call and all he said was that he was so sorry for everything that happened, that he wanted me to return to him, that he loves me so much. I was so happy and went to him, that was how we started living together happily again. Since then, I have made promise that anybody I know that have a relationship problem, I would be of help to such person by referring him or her to the only real and powerful spell caster who helped me with my own problem and who is different from all the fake ones out there. Anybody could need the help of the spell caster, his email: spiritualherbalisthealing@gmail.com or call him +2348164728160 you can email him if you need his assistance in your relationship or anything. CONTACT HIM NOW FOR SOLUTION TO ALL YOUR PROBLEMS

ReplyDelete